As a physicist working with femtosecond lasers and large spectroscopic datasets, I have always been drawn to technologies that push the limits of what is computable. Quantum computing stands out because it targets problems that are brutally hard for classical machines, such as accurate simulation of strongly correlated molecular systems and complex optimization landscapes.

Quantum Computing: Comprehensive overview and key takeaways

In late 2025, real progress is finally emerging beyond the early NISQ-era optimism. In this post, I share a grounded view of where quantum computing actually is, why it matters for fields like chemistry and materials science, and how physicists transitioning to industry can position themselves at this frontier.

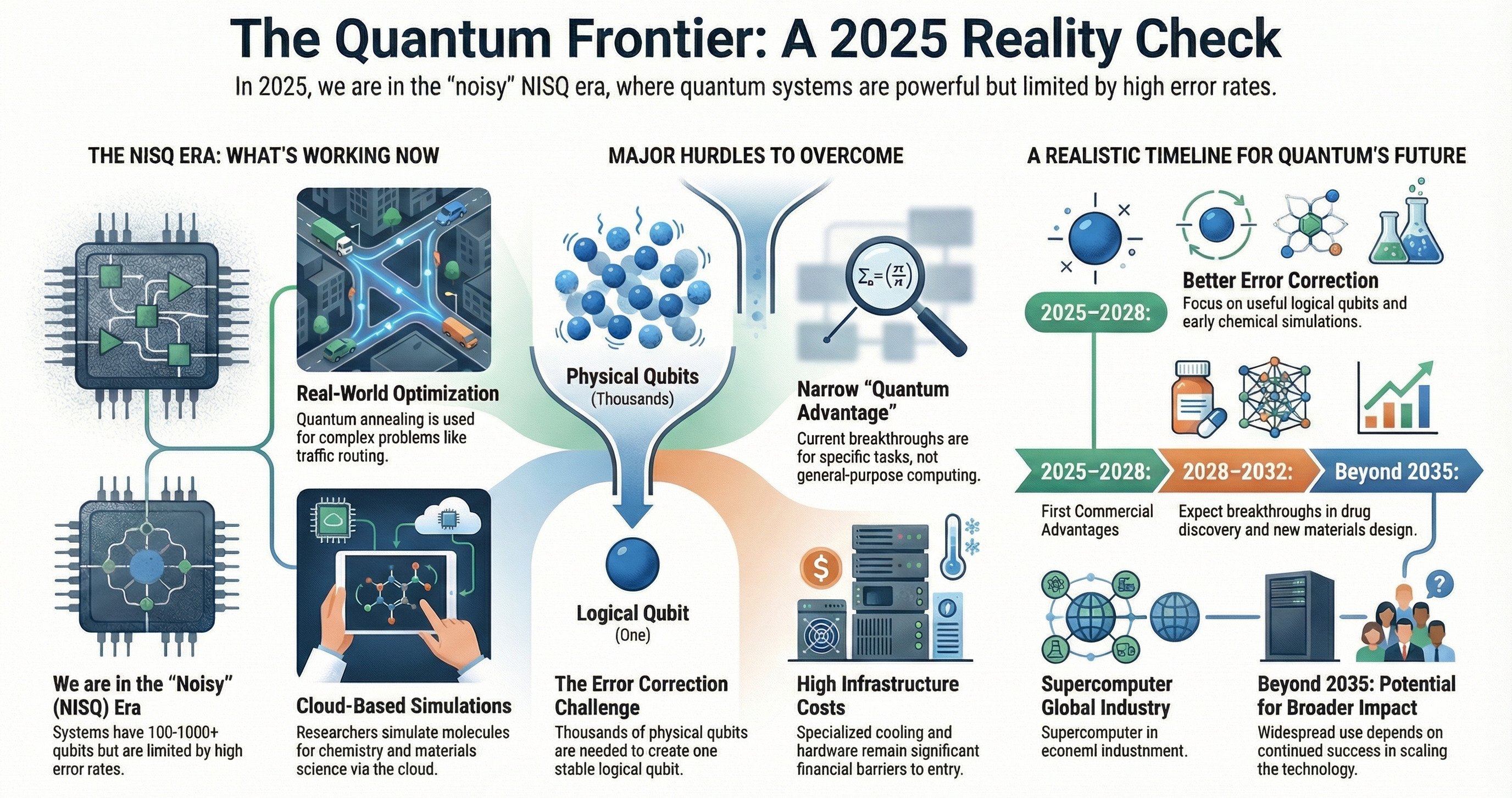

Current reality in late 2025

2025 marks a shift from "demo qubits" toward early logical qubits and credible roadmaps for fault-tolerant systems.

Key milestones that shape the current landscape:

- IBM introduced the Nighthawk processor, a 120‑plus-qubit chip with a high-connectivity topology and improved control electronics designed to run deeper circuits with lower error rates.

- IBM's experimental Loon processor demonstrated the key hardware components required for high-efficiency quantum error correction using qLDPC codes, plus real‑time decoding in under 480 ns on classical hardware.

- Google's Willow processor showed "below-threshold" behavior for surface codes, where increasing the code distance leads to exponentially reduced logical error rates rather than amplifying noise.

- Microsoft and partners (Quantinuum, Atom Computing) demonstrated highly reliable logical qubits with logical error rates hundreds of times lower than underlying physical qubits, and commercial neutral‑atom machines with up to 28 logical qubits integrated into Azure.

- Neutral‑atom and ion‑trap platforms, including systems like Quantinuum's Helios, now routinely report two‑qubit gate fidelities above 99.8%, a crucial threshold for scalable error correction.

Practical takeaway: the field is still pre–fault‑tolerant, but the gap between theory and hardware is shrinking faster than most pessimistic forecasts predicted.

Photo by Alexandre Debiève on Unsplash

What error correction progress really means

Error correction is the difference between toy demonstrations and useful quantum computers.

In 2025, several things changed:

- Surface code experiments reached the regime where logical error rates improved as code distance increased, confirming operation "below threshold" on real devices.

- IBM's Loon architecture showed that high‑connectivity layouts and fast classical decoders for qLDPC codes can be implemented on realistic superconducting hardware.

- Microsoft's qubit‑virtualization system, combined with ion‑trap and neutral‑atom hardware, demonstrated logical qubits with error rates improved by factors of 800× or more over physical qubits in long experimental runs.

From a physicist's perspective, this means we are no longer just fighting noise; we are beginning to engineer it in a controllable, quantitative way.

Applications I am watching closely

My own background in molecular clusters and microsolvation makes quantum simulation of strongly correlated systems the most compelling near‑term application.

Areas where quantum computing is already showing practical promise:

- Quantum chemistry and materials - Better approximations to ground and excited states for strongly correlated systems, such as transition‑metal complexes, catalysts, and battery materials. Early hybrid algorithms that combine quantum subroutines with classical post‑processing for reaction energetics.

- Optimization and logistics - Quantum‑inspired and quantum‑assisted optimizers applied to portfolio optimization, traffic routing, and supply‑chain planning, including experiments reminiscent of Volkswagen's early quantum traffic routing pilots.

- Machine learning and generative models - Small‑scale quantum machine learning models for feature maps and kernel estimation in high‑dimensional spaces. Experimental quantum generative models for molecular design and anomaly detection in physical systems.

Photo by Louis Reed on Unsplash

Challenges that still dominate

Despite the progress, several hard problems remain:

- Scale of logical qubits - Depending on the code and hardware, a single logical qubit can require anywhere from a few hundred to tens of thousands of physical qubits. Even if two‑qubit fidelities are around 99.9%, large‑scale fault‑tolerant machines may need millions of physical qubits and highly efficient decoders.

- Real-time decoding and infrastructure - Classical decoding for large‑distance codes requires low‑latency hardware and optimized algorithms that can keep up with gigahertz‑scale cycles. Cryogenic systems, control electronics, and quantum networking for modular architectures all add engineering overhead.

- Algorithmic maturity and narrow advantage - Many proposed speedups assume idealized conditions or asymptotic regimes that are far from current devices. Real‑world advantage is likely to appear first in narrow, high‑value niches.

A realistic timeline (my view)

Putting current roadmaps and experimental trends together, a conservative but optimistic timeline looks like this:

- 2025–2027: Increasingly robust logical qubits with verified below‑threshold behavior on multiple platforms. Hybrid quantum–classical experiments in chemistry and optimization that produce results competitive with specialized classical methods on narrow problem instances.

- 2028–2030: First recurring commercial “edges” in materials and drug discovery, where quantum workflows become part of the toolchain. Modular architectures and early quantum networks connecting smaller processors.

- 2030+: Potential for utility‑scale quantum computers that can routinely outperform classical supercomputers on a set of industrially relevant tasks.

Why this matters for transitioning physicists

For physicists moving toward data, AI, or applied R&D roles, quantum computing offers a convergence point between physical intuition and computational thinking.

In my case, years of working with ultrafast spectroscopy, UHV, and complex experimental setups taught me how to reason under noise, calibration drift, and hardware constraints. Handling large spectroscopic datasets pushed me into Python, numerical methods, and statistical modeling, which map naturally to quantum algorithm analysis and simulation.

From a DACH perspective, Germany and the broader EU are investing heavily in quantum technologies, with national and European programs spanning hardware, software, and applications. There is strong demand for people who combine deep domain knowledge (chemistry, physics, materials) with enough computational maturity to work with hybrid quantum–classical workflows.